2022 marks the centennial of Mystic’s iconic bascule bridge. In keeping with the town-wide celebration of this anniversary, this exhibition features the historic and artistic importance of this masterpiece of architecture, its predecessors, and the Mystic River itself. These defining features of Mystic are represented here by sixty works of art, including paintings, prints, ceramics, and ephemera from MMoA’s permanent collection augmented by holdings on loan from private collectors and fellow institutions.

Featured Image Credit: Y. E. Soderberg (1896-1972), Mystic River View, Bascule Bridge, undated, watercolor on paper. Collection of Mary Boland.

—

THE INFLUENCE OF THE MYSTIC RIVER

The white settlers of Mystic in 1654 could not have fully anticipated the Mystic River’s strategic location. Equidistant between Boston and New York, with deep water, sheltered anchorages, and proximity to old-growth forests as a source of lumber, the river was perfectly situated to capitalize on a booming shipbuilding industry. Less than five miles long from its head at Whitford Brook in Old Mystic to its mouth in Noank Harbor, this tidal estuary was home to 11 shipbuilding sites—twice as many as in Boston Harbor during the same period, despite Boston’s exponentially larger coastline and population.

More than 1,400 vessels were either built or repaired along the Mystic River since 1700, serving fishing fleets in New London and Stonington, a local whaling industry, and international shipping out of ports from New London to New York. Mystic-built clipper ships, designed for speed, were in especially high demand during the mid-nineteenth century. Mystic produced 21 such vessels between 1850 and 1860. They represented only 4.4% of the 446 fast-passage ships during that decade; yet 11% of the quick passages from North Atlantic ports to San Francisco during the Gold Rush, making record time on three occasions.

Mystic River shipyards operated at full capacity during the Civil War. Mystic produced more steamboats between 1861 and 1865 than any other New England port, but production fell sharply in the following years with the increased demand for large, iron-hulled ships. Without a ready supply of iron to supply this demand, local industry turned to lucrative mills and factories, and localized fisheries.

THE INFLUENCE OF THE MYSTIC BRIDGE

The Mystic area was originally settled by members of the native Pequot and Mashantucket tribes. Anglo-Europeans settled at the head of the river, near the modern-day intersections of Routes 27, 234, 184, and River Road in Old Mystic. As these communities and their industries spread down the Mystic River over the following 18th and 19th Centuries, the ability to cross from one bank to the other proved increasingly important.

People who needed to traverse the river had three options. They could take a long detour around the head of the river, they could ford “the narrows” (near the present day I-95 bridge), or they could pay Joseph Packer two pence to be ferried between Packer’s Wharf and Pistol Point, slightly further downstream from MMoA. Despite being the most convenient of these three options, Packer’s Ferry operated only irregularly between 1756 and 1818, according to the whim of its proprietor. Soon after Joseph Packer passed away, Mystic’s residents petitioned the Connecticut General Assembly for the right to build a proper bridge across the Mystic River.

The Mystic Bridge Company was charted in 1819 and hired Nat Canada to build a wooden bridge near the present-day location. The 1819 bridge was privately owned by Mystic Bridge Company shareholders who levied a 25-cent toll for four-wheeled vehicles.

The construction of the bridge profoundly changed the geography of downtown Mystic, and by extension the main travel route along the Boston Post Road. Before 1819, most commerce was centered around Packer’s Wharf at the base of New London Road. When the bridge opened several hundred yards upstream, commercial establishments relocated to Main Street, which became an important thoroughfare along US Route 1, connecting Maine and Florida.

Five total bridges were constructed between the east and west banks of the Mystic River between 1819 and 1922.

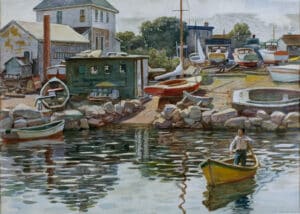

A DESTINATION FOR ARTISTS

“Mystic has long been a centre for landscape and marine painters. And most justly so, for the country that surrounds this picturesque village is more than usually rich with the motive of every description. Whether it be the woods or pasture land, sweeping flats or rolling hills, fishing village scenes or open sea, here the painter finds what he loves…”

— The New London Day, Aug 16, 1917

The Mystic River, and the bridges that have spanned it over time, were key to Mystic’s growth as a summer destination for artists—a trend that continues to this day. Just as Mystic’s location at the head of the river perfectly suited a booming maritime economy in the 18th and 19th Centuries, the growing town’s position midway between Boston and New York proved ideal for artists seeking remote settings of great natural beauty at the turn of the 21st century.

In 1922 Mystic’s current bascule bridge formed the final link in the country’s new highway from Maine to Florida, providing more access to the area than ever before. Some of the early members of the Mystic art colony and Mystic Art Association, such as Lorinda Dudley and G. Victor Grinnell, were locals, but the vast majority, like George Albert Thompson, Lester Boronda, Arthur Meltzer, Y.E. Soderberg, and Harve Stein, started as summer visitors to the area. Many of these artists moved here permanently, captivated by unspoiled landscapes such as those depicted in the paintings at right, to be found along the Mystic River from its headwaters in Old Mystic to its mouth on Fishers Island sound, flanked by Noank and Mason’s Island.

—

Thank you to the lenders who made this exhibition possible:

The Connecticut Department of Transportation

The Greater Mystic Chamber of Commerce

Lyman Allyn Art Museum

Mystic River Historical Society

Mystic Seaport Museum

Noank Historical Society

Mary Boland

Jonathan C. Sproul

Support for this exhibition was provided by the Kitchings Family Foundation, and by CT Humanities (CTH), with funding provided by the Connecticut State Department of Economic and Community Development/Connecticut Office of the Arts (COA) from the Connecticut State Legislature.